Known since 1992, the French diet is high in saturated fats, a risk for coronary heart disease (CHD), yet they have less than half the CHD-related deaths compared to the US, Sweden, and the UK. High intake of wine, thought to be 57% of alcohol consumption in France, may contribute to this disproportionately low frequency of CHD representing the French paradox. However, heavy alcohol consumption is associated with increased risk of heart attack, arrhythmia, hypertension, and sudden death. This raises the question; How does wine consumption improve cardiovascular health?

Wine, particularly red wine, contains high levels of phenols. One phenol, resveratrol, may contain cardiovascular protectant properties. It inhibits oxidative stress caused by free radicals, preventing cell damage or death. Resveratrol appears to increase lifespan and promote healthy aging. Fruit flies, fish, and nematodes given resveratrol increase their lifespan significantly! In humans low to moderate amounts of wine consumption are associated with decreased cardiovascular- and cerebrovascular disease-related deaths.

Moderate consumption of wine is also associated with lower instances of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Normally, proteasomes are responsible for degradation of damaged and aggregated proteins such as Aβ, but their activity is impaired in AD. Oxidative stress inactivates proteasomes, which can be prevented with resveratrol administration in disease-model cell cultures. Administration of resveratrol in vitro correlates to increased intracellular degradation of Aβ by proteasomes, suggesting that moderate wine consumption may decrease one’s likelihood of developing AD. Synthetic resveratrol supplements are new to the field and require further research.

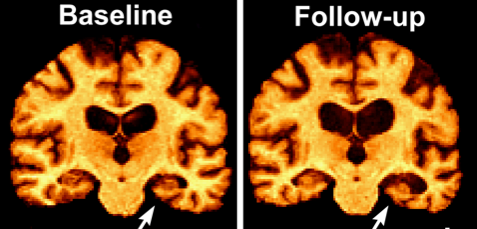

One year of resveratrol supplementation (500-2000 mg per day) slowed decline in cognition and function compared to placebo. Yet other studies found no difference with supplementation over 52 weeks. Larger studies over a longer duration are needed. Pterostilbene, a synthetic resveratrol analog, has much higher oral bioavailability and blood-brain barrier permeability warranting further research. Resveratrol administration correlates with decreased central nervous system (CNS) deposition of Aβ, and increased brain shrinkage in AD patients as a product of reduced neuroinflammation.

Resveratrol benefits a variety of other physiological functions, too. It delays or prevents cell death in a variety of cell types, decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation, reduces risk for hypercholesterolemia, maintains glucose homeostasis in diabetes, and promotes tumor suppressor gene expression. In rat models of Lewis lung carcinoma, resveratrol decreases tumor size, weight, and metastasis, indicating a diverse range of effects on chemoprevention. It has powerful effects on energy metabolism. In mice, administration increased aerobic capacity as evidenced by increased running time and oxygen consumption in muscle fibers. Its effects on energy metabolism might also minimize damage from secondary spinal cord injuries. Further research in human models is needed to validate it as a therapeutic.

While resveratrol’s impacts on cognition and AD are inconclusive, it has potential to benefit health in a variety of other ways, which may justify a glass of red wine every so often. If you can’t drink wine, resveratrol is also present in a number of foods, including grapes, peanuts, soybeans, apples, and pomegranates. Red wines contain concentrations between 0.361-1.972 mg/L, meaning that one would have to drink many bottles of wine to achieve the hypothesized therapeutic dose (TD) of 1 gram per day. Even including resveratrol containing foods such as peanuts (0.03-0.14 μg/g) and apples (400 μg/kg) does not reach the TD. However, these measurements only account for unbound resveratrol. Food and drinks containing pure resveratrol also contain molecular constituents and resveratrol glucosides which occur in higher concentrations and, in some cell culture and animal studies, show higher potency than resveratrol itself. These molecules may actually be the driving force behind the French Paradox, but focused research and clinical trials will be required to confirm this hypothesis.

There are also supplemental tablets derived from Japanese knotweed containing a therapeutic dose of concentrated resveratrol. Unfortunately, research has shown that these supplements are a less effective source of resveratrol as it’s bioavailability and absorption is enhanced by the food matrix present in its naturally occurring forms. Regardless, with so many beneficial impacts in the body and no serious adverse effects we could all stand to increase our resveratrol intake – whether it comes from a glass of red wine, a handful of peanuts, or a supplement. This week, go out and live like the French!